What’s a room?

Space within a building separated by walls according to dictionary. And if you peruse a few popular dungeons you’ll find plenty of these. But then, sometimes you get something interesting like caverns, rocky tunnels, or courtyards. Typically, they’re still referred to as ‘dungeon rooms’.

What we really need to know is: from a meta, dungeon-designey perspective, what is a room?

In Rules 1 & 2 we defined doors, not as the typically wooden and openable partitions, but as signals for players to alert them to their options for moving through the dungeon space. From there we translated that definition into one that works in an outdoor dungeon. Here, we’re going to do the same thing for rooms. But first, we’re going to a go on a little tangent. Rather I should say, you’re going to go on a little tangent. Click here.

What you just experienced is Zork, one of the precursor’s to many of the video game rpgs you’re probably familiar with. Taking obvious inspiration from D&D, the game was actually going to be called ‘Dungeon’ until TSR shut that down. If you didn’t get the chance to play it a bit, Zork is a text adventure game. They were usually played in a command prompt, wherein the system would tell you in a short paragraph what was around you, and you would enter in what your character did in response using a verb and noun. Not too far off of from ttrpgs, huh?

Zork holds the key to breaking down rooms into their true meta abstract form. See, Zork is situated as a grid of areas, or rooms, and using north, east, west, and south, you move from room to room. Eventually, you’ll probably run into something interesting. Something you can interact with. But you only get the prompt that there’s something to interact with when you’re in the right room to do so, the right room to see the interesting thing. In a nutshell, that’s what dungeon rooms are.

Rooms are devices that tell your players what they can interact with at a given point in time.

The versatility of rooms is that they communicate this info for both the present room, where players are, and all previous rooms through object permanence.

Room A with the red carpet holds a bookcase and a desk containing a bloody knife. Room B with the blue carpet holds a dead body. The players are in Room B. They know that the dead body is in front of them, and they can interact with it. If they want to interact with the bloody knife, they know they need to go back to the red carpet room. Room A.

Really, dungeon rooms are glorified rpg menus.

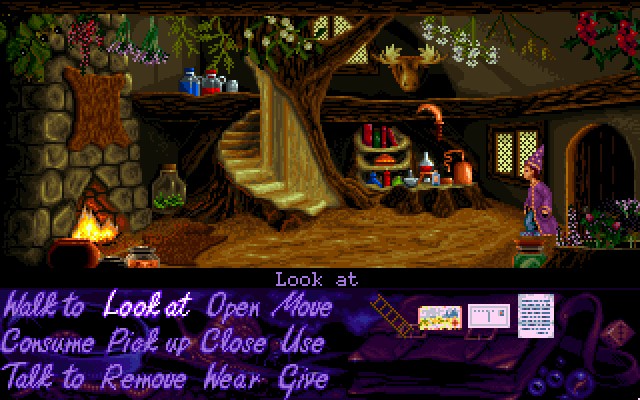

Anyone remember point and click adventure games?And if that’s the case, what’s stopping you from having a ‘menu’ of options in an outdoor space instead of an enclosed area?

Well... a few things. In the next couple of posts, we’ll go into what those things are, and how I solve them.